Following the high-pressure sales and production figures that Curtiss had become used to during the years of the First World War it was expected that the company would still be flooded with orders both at home and abroad once the fighting ended.

Curtiss saw their military order numbers drop sharply from November 1918, as did the rest of the aviation industry. Curtiss had nine production plants running at this time, thanks to the popularity of the Jenny and its flying boat designs, yet shortly after the war all but the Buffalo and Garden city plants had been shut down. There was very limited military interest in 1919 and the expected boost in civilian sales after the war failed to appear in those early years.

Curtiss’ hopes were not helped by the fact that the government had no immediate desire to upgrade the aircraft serving with the armed forces as they saw no immediate need for more advanced, up to date aircraft now the war had been won. This sudden, catastrophic drop in business led to many aviation firms going out of business in the early 20s, it certainly looked like a challenging time ahead for Glenn Curtiss and his team.

So how did Curtiss manage to survive the drought that many of its contemporaries did not. Well, as mentioned in the earlier post on the Jenny, they managed to buy back $20,000,000 worth of surplus aircraft and engineers for the government of $2,700,000. A fraction of the cost would be an understatement. While a number of these aircraft needed extensive restoration work, some were still in “as delivered” condition. Curtiss was able to sell many of these machines at wartime prices throughout the 1920s, helping to keep the company afloat.

The surplus aircraft that Curtiss purchased from the government were not just their own designs. Many of the early aircraft sold by Curtiss following the war were in fact modified variants of other companies aircraft. The Standard J1 for example. Curtiss rebuilt many of these from damaged surplus aircraft and sold them at reduced rates, they also developed specialised Mail carrying variants to appeal to the emerging air mail movement.

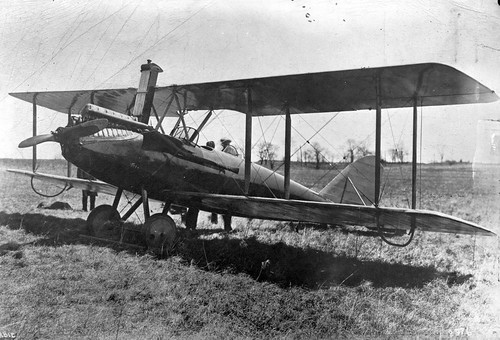

The Oriole (above) was to be the first new Curtiss design following the war. A tractor bi-plane it still looked very much like something out of WWI, powered by an OX-5 with upright exhausts out in front of the cockpit. Though it did boast side by side seating for two passengers up front, much like later Curtiss designs which would follow. None-the-less it was certainly a neat looking design and Curtiss expected great success. Ultimately though it could not compete with the cheap surplus aircraft on the market. This was one of the first aircraft to make use of an electric starter.

Further flying boat designs were produced, such as the Seagull, a refurbished Military flying boat powered by a 160hp engine.

An imposing design and Curtiss’ first attempt at an airliner, came in the shape of the Eagle (below) in 1919, this tri-motor biplane shows the graceful lines that the classic bi-plane fighters of the 30s would soon become renowned for.

The next series of Curtiss aircraft saw the company refining the idea of a bi-plane fighter, while trying to produce civilian variants on the side. Notable models included the Carrier Pigeon, a somewhat ugly, boxlike bi-plane designed as part of a 1925 US post office completion for a new maiplane. The post office ended up buying most prototypes entered so this machine did see service though only three examples were ever built.

Following the relative success of the Carrier Pigeon, a civil variant was developed, known as the Lark. This new machine was effectively a scaled down version of the Pigeon and looked a lot more streamlined as a result. It could take up to four people, two side by side in the from and back cockpits. It also had the flexibility to be converted into a Mail Plane if the need arose.

It was in 1927 when Curtiss would start to show signs of its 1930s classic designs. In response to a Navy fighter competition the company unveiled the F7C-1 Seahawk. A radial powered bi-plane with slightly swept back wings and a single seat. This machine was powered by a 450hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp. The Navy was very impressed by this new design and subsequently ordered 17 production examples.

A name which is very familiar to fans of WW2 aviation is the Helldiver. But Curtiss had an earlier aircraft with the same designation. This was, much like its younger relative a dive-bomber, in this case a two-seat bi-plane example. Though the airframe was designed as a dive-bomber its only service was a limited run in a higher unit before it was assigned to reserve units by the mid 1930s. This design first flew in 1928 and progressed through a number of variants and designations throughout the 1930s.

There is one final design I have decided to include in this whistle-stop tour of the 1920s. The XP10. This aircraft shared much with the classic 20s racers as well as the Hawk Biplanes that had become common place. This aircraft featured a streamlined fuselage, thanks to the inline Curtiss V-1370-15 up front. and a traditional biplane arrangement. Aside from the fact the top wing was two separate pieces which tapered to the fuselage, providing the pilot with forward vision as well as clear views above. Unsurprisingly this aircraft was designed with the pursuit role in mind, specifically for high speed at high altitude. It certainly looks the part on the ground. The design achieved 215mph at 12,000ft but was plagued by the wing surface radiator system, which led to the Army rejecting the design. This unique airframe only clocked up 10 hours total flying time before being scrapped.

The above summarises the trials and designs that Curtiss endured throughout a challenging decade for the aviation industry. Of course alongside the designs mentioned above the iconic Hawk line began and the firm was building a good reputation with its racing activity. I’ll be looking at both of these areas as part of the 1930s posts, where Curtiss started to progress towards the WW2 monoplanes.

All photos above were sourced from the San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive and the source for each image can be find by clicking them.